(originally published by Weaver Industries, Inc.)

Synthetic or man-made graphite is produced in hundreds of different grades. Most grades have been developed for specific applications, and each grade has its own set of properties associated with them. Typical properties include grain size (or particle size), density, electrical resistance, flexural strength, compressive strength, hardness and operating temperatures.

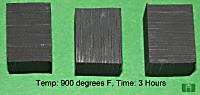

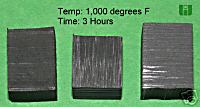

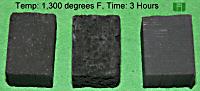

This testing was specifically focused on operating temperatures in air. Most graphite and carbon perform well in an inert atmosphere, such as argon or nitrogen, to prevent the oxygen from attacking the graphite. The process that occurs when using graphite at high temperatures in air (with oxygen present) is known as oxidation. This test involved three individual grades with the same basic grain sizes and dimensional sizes. The pieces were placed in a preheated kiln at the noted temperatures for the noted length of time. The kiln was not air tight so we could see the results of the oxidation. The grade on the right was a grade that has special properties to reduce oxidation in a higher temperature oxygen environment. The base materials are selected to provide better protection from oxidation and then treated (oxidation retardant penetrated throughout the material).

The photos above show that very little has changed in the graphite up to 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit for a time of 3 hours. Even though there is no real visible oxidation, all untreated graphite will begin oxidizing at around 800 degrees Fahrenheit. It may start as subtle changes like weight loss and minor deterioration.

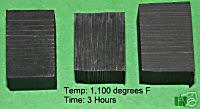

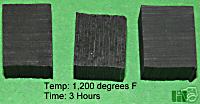

By the time temperatures reached 1,100 to 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit, the untreated material began to show significant changes. Please note the pitting, especially in the center piece.

As the temperatures began to rise, the oxidation in the untreated materials became very obvious. To continue the testing to see what would happen at higher temperatures, the time was cut to 1-3/4 hours. Please note the way the untreated pieces actually started to dissolve in the photo of 1,400 degrees F for 3 hours. Working at these temperatures, the graphite actually had an orange glow. The graphite has serious pitting, and actually starts turning to dust and simply eroding away.

Please note the way the grade on the right was able to maintain the original size and shape at these extreme temperatures. This temperature was actually higher than what was suggested as the maximum operating temperature, however, it did perform very well in this very simple test.

While working with glass and other high temperature materials, if you notice that the graphite is actually heating to an orange or red glow, you will experience premature failure of the graphite tools from oxidation. When evaluating the material to purchase, please specify that you are experiencing these problems, and need a grade that is capable of withstanding a higher working temperature in oxygen. Also note that the extra process to produce the oxidation resistant materials adds additional expense to the base materials. You will need to evaluate the extra life of the material versus the added expense in purchasing the more expensive materials.

A side note that I also feel is worth mentioning: when using graphite with glass or metals, the actual temperatures of the glass or metal may be higher than what my tests used. However, the heating can be more concentrated in a cavity that is completely covered by the glass or metal. In these instances, the hot glass or metal will actually shield the graphite from air (oxygen) and oxidation is not as big of a concern.

I hope you find this information helpful when using graphite or evaluating graphites.

Weaver Industries - Shaping your Needs in Graphite!